This is a guest post by Allison McCarthy. Allison is a regular blogger for Ms. and Girl with Pen.

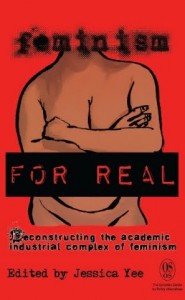

Feminism FOR REAL: Deconstructing the Academic Industrial Complex of Feminism edited by Jessica Yee (Canadian Centre for Public Policy)

If you’ve ever been burned out by Women’s Studies classes, confused by the feminist blogosphere’s intellectually elitist hierarchies, or rendered invisible by mainstream media depictions of What A Feminist Looks Like™, we should talk about it. For many of us, we don’t know where to start talking, or how, or even to whom we should address the issues of inequality which plague so many feminist and social justice movements: racism, sexism, ableism, classism, homophobia, ageism, cissupremacy, colonialism – a mere sampling from the makings of kyriarchy and the treacherous systems of domination and subordination which police our identities, our privileges and our oppressions. Jessica Yee’s Feminism FOR REAL: Deconstructing the Academic Industrial Complex of Feminism is an unflinching, complex look at how capital-F feminism has oppressed, silenced, and maligned people on the margins of society.

In some respects, Feminism FOR REAL is a natural extension of the conversations in Yee’s previous work, Sex Ed and Youth: Colonization, Sexuality and Communities of Colour (CCPA 2009). Many of the contributors in Feminism FOR REAL self-identify as Indigenous and offer powerful essays confronting sexism, racism, and colonialist occupation. But in other respects, the book feels like a continuation of AnaLouise Keating and Gloria Anzaldúa’s feminist dialogues in this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation (Routledge 2002). Like this bridge we call home, Yee’s book casts a wide net over a cross-dialogue from authors of diverse backgrounds: multi-gender, able-bodied and dis/abled, old and young, people of color and white. Ultimately, the multiplicity of voices and experiences in Feminism FOR REAL offers a rich tapestry of feminisms for readers to listen, learn, and engage.

There’s something to consider when comparing the curvaceous and fat, brown belly depicted on the cover of Feminism FOR REAL to 2007’s graffiti splash of Full Frontal Feminism across a white, taut belly. And if you’re curious about the book’s title, Yee defines the term academic industrial complex of feminism in her introduction as “the conflicts between what feminism means at school as opposed to at home, the frustrations of trying to relate to definitions of feminism that will never fit no matter how much you try to change yourself to fit them, and the anger and frustration of changing a system while being in the system yourself” (13-14). Yee’s editorial direction eschews traditional models of writer-audience dialogue; she doesn’t condescend to Native youth in Sex Ed and Feminism FOR REAL doesn’t talk down to academic feminists. Mixing AQSAzine’s poetry (“Muslims Speaking for Ourselves”) with incisive dialogues like the stand-out “Resistance to Indigenous Feminism,” co-authored by Krysta Williams and Erin Konsmo, Yee provides a steady pace of ideological writings in a variety of literary styles. And there’s rarely a dull moment to be found throughout.

The anthology doesn’t always get it right when it comes to inclusivity: in several essays, there is repeated use of ableist language such as “blind” and “blindsided.” RMJ at Deeply Problematic has a great post explaining how this term is often used in social justice communities to discuss privilege, but the word “blind” and its various permutations actually perpetuates oppression. Louis Esme Cruz’s “Medicine Bundle of Contradictions” did a great job of centering issues on disability (as well as indigenous rights, gender identity, and self-love/love of community). But overall, I think, my criticism of these missteps in language is a compassionate take: we each and all have privilege in some areas and face oppression in others, so our journeys of un-learning damaging ideas, practices, and language involves both concentrated effort and unintentional mistakes. And yes, I realize that my own compassion, in this instance and others, also goes hand-in-hand with my able-bodied privilege.

In an online interview, Latoya Peterson, owner/editor of Racialicious and author of the Feminism FOR REAL essay “The Feminist Existential Crisis (Dark Child Remix),” reflected on the completion of publishing her piece for the book. “I feel a lot more validated in other spaces where I am practicing feminism and applying it,” she wrote. Her advice for young feminists? “Do something else besides feminism. I’m serious. The feminist blogosphere is oversaturated in my opinion. Please, find something else you love and take feminist theory there. It gets lonely over here in tech and video games – I have a great crew of other feminists but we are a little island in a vast sea. We need more feminist minded business bloggers, feminist theory wielding finance bloggers. Labor organizers with a feminist lens blogging. Can you imagine what Deadspin (the sports blog) would look like with a feminist on staff? Restructure writes about science, tech and feminism – join her! Publish a blog doing literary criticism with a feminist lens! Take on The New York Times! Talk about class issues and feminism. Whatever it is, apply your feminism in a different space.”

Clocking in at a mere 176 pages, Feminism FOR REAL is a minor publishing miracle – a book that speaks truth to power by challenging the status quo of white supremacy, class privilege, heteronormativity, and other regrettable –isms within the scope of feminism. Editor Jessica Yee examined so much of what is loathsome about our current mainstream feminist representations and then published her anthology with a union-based independent press that aligned with her core political values. Feminism FOR REAL deserves recognition for its efforts to educate, challenge, and incite change. If we’re ever to make the jump from feminist theory to our complicated realities, I hope we can answer the book’s call to be just a little more understanding, a lot more open to our lived experiences, and yes, a little more real.

**To buy a copy of the book and support independent publishing media, please see here **