In response to Lauren’s suggestion a few days back that I write a post about something historical, I thought I would share with all of you a brief glimpse into that which supposedly occupies my day-to-day life. Namely, my dissertation.

The main focus of my dissertation concerns the activities of naturalists in the Pacific Northwest and how their work was related to the larger project of imperialism in the region in the early 19th century. In order to set the stage for this I need to spend some considerable time discussing the main economic enterprise associated with European (and, to a degree, American) imperialism in the Northwest, which in this case is the fur trade. Globalization is a term in much use these days, and while some globalizing institutions and processes are fairly recent, globalization writ large is not new. There is no way I can really do justice to the history of the fur trade here, but it has long been a topic worthy of historical consideration.

The northwestern coast of North America, and the land adjacent to it, was one of the last regions of the continent to be explored by Europeans. The Northwest was, in a sense, an imperial convergence zone in that it became significant to the interests of European powers – primarily Britain, Russia, and Spain – by the late 18th century. The Russians had established themselves in Alaska and were looking to expand southward. The Spanish, who sent out expeditions northward from Mexico since the 1500s, grew increasingly nervous about both the Russians and increased British activity in the Pacific and attempted to strengthen their claims to the Northwest through two expeditions sent to the Northwest in the mid-1770s. The Spanish practice of keeping their travels secret, however, meant that competitors, especially the British, did not recognize Spanish territorial claims. The Royal Navy’s most significant journey to the Northwest in the 1770s was led by Captain James Cook, with the objective of finding the legendary Northwest Passage.

Cook failed to find the Northwest Passage, and grew to doubt that “such a thing ever existed.” What Cook and his sailors did find was something else that turned out to be nearly as valuable: sea otter pelts worn by high-status members of indigenous tribes with whom they came into contact on what is now Vancouver Island. Cook’s men exchanged goods for sea otter pelts, but were not aware of their value until Cook’s ships (though not Cook himself, who was killed during a skirmish in Hawaii in 1779) sailed into the Chinese port of Canton and discovered that the Chinese were willing to pay very high prices for sea otter furs.

British merchants organized several more expeditions to the Northwest during the 1780s with the goal of cashing in on the lucrative Chinese fur market. While these expeditions met with varying degrees of success, they established a long-term economic relationship between Europeans (and later, Euro-Americans), indigenous peoples, and the land itself.

The native peoples of the Northwest Coast had developed sophisticated, hierarchical societies in which material wealth conferred prestige upon those who could acquire it. Hence, Northwest natives were assiduous traders and were linked into extensive trading networks that spanned along the entire Northwest Coast and far into the interior of North America. The arrival of Europeans presented another opportunity for trade and indigenous peoples sought to take advantage of this. Typically, Europeans received such items as food, water, and furs and in return natives demanded metal goods, especially copper, which they highly prized.

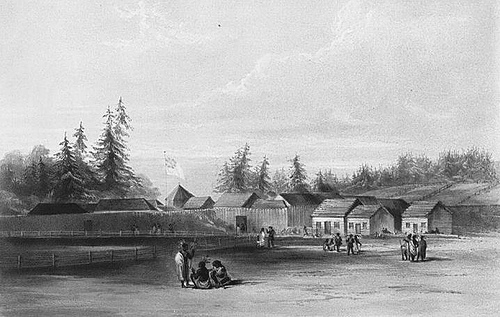

Over the course of the next sixty years, this relationship grew in importance and complexity, with significant consequences for both Europeans and natives. Europeans found themselves in the position of have to accommodate native peoples’ terms for trade, as natives outnumbered Europeans and were far better acquainted with the territory. Yet Europeans were still able to earn considerable profits from furs, which only increased their desire for more and created the context for a permanent presence in the region. By the first decade of the 1800s, the maritime (sea otter) fur trade had come to be controlled by American traders, but the British, through firms like the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC, founded in 1670 and still in existence today) controlled the land-based fur trade (dealing mostly in beaver pelts) that extended across all of North America, and which made these companies virtual “rulers” of the lands in which they operated. Beaver pelts were the main component in the manufacture of felt, which in turn was made into hats that were fashionable all over Europe. The British constructed a capitalist network that stretched from China across the Pacific to North America, and across the Atlantic to London. This trade established an extractive economy in the Northwest (which eventually included raw materials like timber and salmon) and fomented European and Euro-American colonization.

The trade in furs also had far-reaching effects on the indigenous peoples of the Northwest. Native people, who at first traded in furs mainly in the context of their own regional economies, directed more and more effort into meeting the European demand for furs, which oriented native economies toward furs for global export. New social relationships were also established, particularly through intermarriage between European traders and native women. These marriages were encouraged because this created a kinship tie between the fur traders and “upper-class” indigenous peoples, which meant such natives would have favored status in trading relationships. Other consequences were not so benign: Europeans brought new diseases to which indigenous people had no immunity, resulting in very high mortality (up to 80% in some areas), and the gates of the Northwest were opened to white settlement, resulting in violent confrontations between natives and whites from roughly the 1840s through the 1870s.

While today’s globalizing economy differs in significant ways from the mercantilist capitalism of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it is one stage in a long process in which the importance of the humble sea otter and beaver should not be forgotten.