This guest post is a part of the Feministe series on Sexual Assault Awareness Month. abby jean writes for FWD/Forward and at her tumblr, think on this.

Trigger Warning

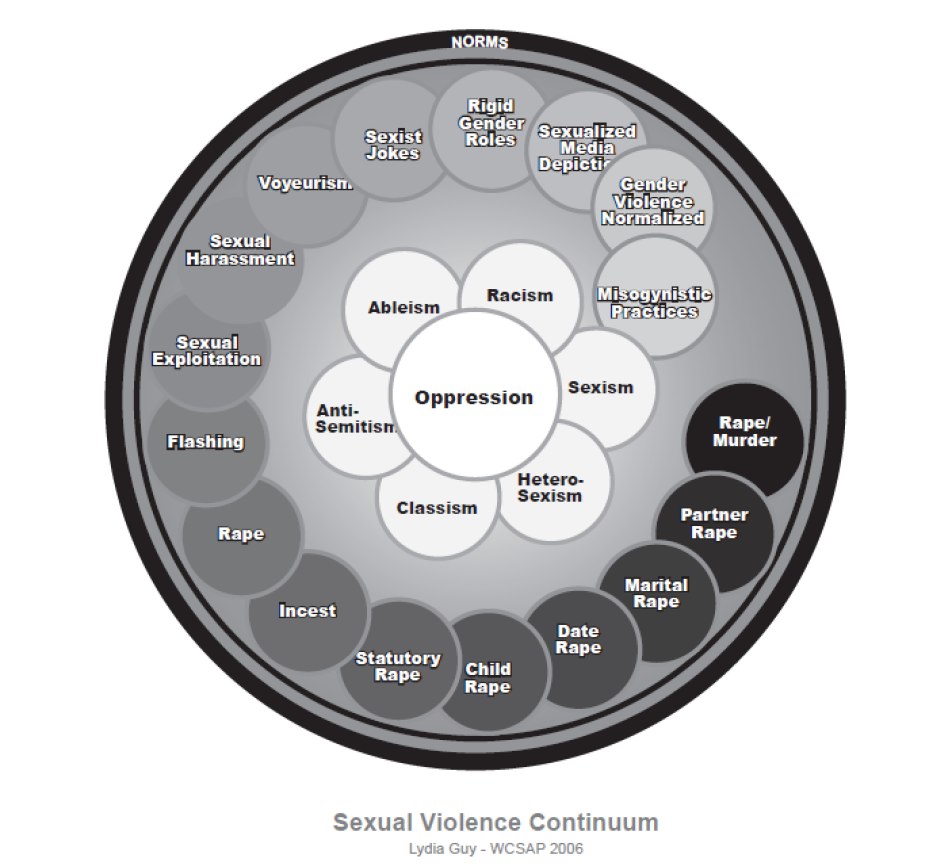

Women with disabilities are more than twice as likely to be victims of rape or sexual assault than women without disabilities. More than twice as likely than what is already a terrifyingly high probability of being a victim of rape or sexual assault. I myself am a woman with a mental health disability who is also a victim of sexual assault, and seeing this statistic always makes my stomach drop and my muscles tense. But when I think about it, what influences that statistic, it makes perfect sense. Rape and sexual assault are crimes of power and control. Women with disabilities are subject to sets of interlocking, intersecting oppressions on the basis of their gender and their disability status. Both gender-based oppression and disability-based oppression separately accept and even encourage abuse and denigration of people in those groups. So of course it makes sense that sexism and ableism would add to each other, reinforce each other’s power, resulting in the heightened vulnerability to assault reflected in the statistics. I find the following chart – taken from a presentation by Nancy Fitzsimons of Minnesota State University – helps illustrate the idea that intersecting oppressions make an individual increasingly vulnerable to gendered violence, culminating in rape or sexual assault:

I’m sure that readers here are familiar with the societal and cultural messages and assumptions that make women vulnerable to sexual assault and rape, so I want to explore some of the components of ableism that interact with and reinforce those sexist tropes. For me, it is always striking to see that for women with disabilities, as is true for all rapes, the vast minority of assaults are done by strangers: 33% of abusers are acquaintances; 33% of them are natural or foster families, and 25% are caregivers or service providers. This echos my own experience – the man who raped me was my boyfriend at the time. And one of the most powerful tools he used against me was my own sense that, as a person with a disability, I was an inherent burden on those around me and so owed an immeasurable debt to anyone who would bother to put up with me. This meant when he demanded things of me sexually, I felt I had no right to refuse. This was colored by my recognition, my insistence, that every woman has the inalienable right to define her own sexual boundaries – but I felt that didn’t apply to me, because I was so worthless, so broken, so less-than, that I didn’t deserve any more.

This theme of dependence and burden is a significant component of ableism. The social model of disability argues that while all people have physical and mental variations, it is systemic barriers and societal attitudes that cause some of those variations to be “disabling,” because the world is not set up to accommodate those variations and therefore pathologizes them. (For more, see this post by amandaw at FWD.) For example, a wheelchair user might be unable to get to and from the grocery store without assistance, but only because the local public transit system systemically excludes people with disabilities, not because they are inherently unable to do so. The wide array of socially created dependencies force people with disabilities to be dependent on their families, on their romantic partners, on their caretakers, to function on a very basic level. People with disabilities are less likely to be employed or to be financially independent. Anyone who uses a device to communicate – a computer with speech software, a TTY phone – can be dependent on a caretaker for access. People with disabilities can be dependent on others for access to food, shelter, or even going to the bathroom.

This dependence has two effects. The first is obvious – someone with control over someone’s access to food and water is an extraordinary position to exploit that vulnerability through sexual assault or rape. It will be more difficult for the victim to challenge the assault, report the assault, or leave the abuser’s control when she is so dependent on that same abuser for the fundamental components of her life. Any resistance on the victim’s part can be immediately countered by withholding transportation, medications or medical treatments, communication, and even food and water. When this is combined with the sense of burden and being indebted that is also reinforced by social construction, the caretaker -whether a family member, romantic partner, service provider, or otherwise- is vested with monumental power over the woman with a disability.

In my case, struggling with an overwhelming depression that told me I was worthless and evil and everyone would be better if I were dead or had never existed, my boyfriend provided me with reassurance that I was a person deserving of love, that I need not be a perpetual outcast, and that I had worth and value – all reassurances he explicitly withdrew when I hesitated to comply with his sexual demands. Part of my beliefs came from the depression, but part came from an overwhelming sense that “crazy” people didn’t have very much worth. It came from a friend telling me that my depression made me “broken” and I should come back “when I was fixed.” It was reinforced when someone told me I should be happy I was raped because that was the only way someone was ever going to be with me. It was underlined when, during a particularly bad bout of depression, I was kicked out of campus housing lest I “disturb” other students. The message I’ve gotten was clear – as a crazy person, I do not deserve typical relationships, my needs are less important than the complacency of the non-disabled, and my very existence is intolerable until I’m “fixed” enough to pass as non-disabled. Add that on top of all the messages I get as a woman about my primary worth being as a sexual object and I start feeling fortunate that I’ve only been subject to one sexual assault.

There are a number of other aspects to ableism that make women with disabilities especially vulnerable to sexual assault and rape. Women with disabilities have seen their sexuality be treated as common property. Think of all the caretakers that have gotten court orders to give women hysterectomies on the caretaker’s wishes – that makes a woman with disabilities’ sexuality explicitly the property and control of the family and caretakers (which can also make later rapes in institutions or nursing homes undetectable as the women do not become pregnant). Think of the long history of sterilizing women with mental health disabilities, a history explicitly endorsed by the United States Supreme Court. Think of the skepticisim and distrust that usually meets women with disabilities when they present their lived experience – combine that with the inherent skepticism of society and law enforcement towards rape victims and imagine how hard it is for a woman with disabilities to be believed when reporting these assaults. Police will question why anyone would want to rape a person with a disability, or point out past delusions or hallucinations to undermine the credibility of the victim. My own assault was dismissed by authorities because my emotional intensity while struggling with the onset of my bipolar meant I was categorized as an “overly dramatic” girl already, so was surely exaggerating or over dramatizing the events I recounted.

Thinking about all of this can leave me feeling rather powerless and hopeless. But then I remember that if the increased vulnerability of women with disabilities comes from the interlocking forces of sexism and ableism, all I have to do to combat this is continue fighting those forces wherever I encounter them. Even if not directly connected to social violence, fighting ableism helps undermine the messages which make women with disabilities more vulnerable. Fighting for better public transit to serve people with disabilities can make a woman more independent and less dependent on her caretaker, reducing her vulnerability to assault. Fighting against ableist language or ableist tropes in pop culture helps undermine the messages that could convince a woman with a disability that she doesn’t deserve more than sexual assault. Fighting ableism is fighting sexual assault. And, to extend that, fighting racism and classism and homophobia and trans oppression also fights sexual assault, by fighting the interlocking and intersecting forces that make women more and more vulnerable to rape and sexual assault.

There’s a lot to this topic and this post simply scratches the surface. For more, I suggest this post by Anna and the full presentation by Prof Fitzsimons from MSU (pdf). There are also a number of posts at FWD/Forward on this topic, including the need to provide teens with disabilities access to sexual education, barriers to justice for women with disabilities who are victims of sexual assault or rape, and how disabilities complicate escaping abusive relationships. I of course recommend all of the content at FWD/Forward on ableism in general, which connects to sexual assault and rape for the reasons explored above.