This is a guest post by Laurie and Debbie. Debbie Notkin is a body image activist, a feminist science fiction advocate, and a publishing professional. She is chair of the motherboard of the Tiptree Award and will be one of the two guests of honor at the next WisCon in May 2012. Laurie is a photographer whose photos make up the books Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes (edited and text by Debbie Notkin) and Familiar Men: A Book of Nudes (edited by Debbie Notkin, text by Debbie Notkin and Richard F. Dutcher). Her photographs have been exhibited in many cities, including New York, Tokyo, Kyoto, Toronto, Boston, London, Shanghai and San Francisco. Her solo exhibition “Meditations on the Body” at the National Museum of Art in Osaka featured 100 photographs. Her most recent project is Women of Japan, clothed portraits of women from many cultures and backgrounds. Laurie and Debbie blog together at Body Impolitic, talking about body image, photography, art and related issues. This post originally appeared on Body Impolitic.

Laurie and Debbie say:

A connection of ours who does excellent community work, including in the field of fat activism, has asked us to summarize how we create community involvement (especially diversity of involvement) in our work. Because all of the work we did before Body Impolitic was done before the explosion of social media, much of it would be done differently now–and at the same time, we both believe that face-to-face contact is a profoundly important piece of connecting to any community.

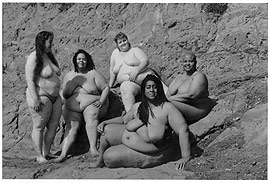

The basis of most of our social change work is Laurie’s photography, which is fine art first, and then becomes a tool for social change. A working artist all her life, Laurie became a photographer initially to create Women En Large. She says, “Artistically, I envision the world in black and white. I never considered being a color photographer. When I’m shooting, I don’t think about the message. I’m too busy working with the model to capture a mood, a facial expression, a pose in which they are comfortable, or a particular combination of visual balances. Each photograph is a stand-alone work of art.”

The way we integrate text with exhibitions of the photographs is one way we bring social change in to the fine art context. All museum and gallery shows have embedded text by models and others. The presence of the text strongly encourages the audience to see the work in a community context, fine-art photographs and related words, showcasing the diversity within an identified group.

Developing appropriate wide-ranging diversity in the photographs, as well as developing appropriate complementary text, requires a great deal of community work. From the very beginning of our collaboration in the United States, we have reached out to the community of people being photographed (fat women for Women En Large, men for Familiar Men, and later Japanese women for Women of Japan).

All three portrait suites are designed to provide an opportunity for people in the group being photographed (fat women, men, women in Japan) to see people “who look like them.” In a media-saturated culture, whether in the U.S., in Europe, in Japan, or around the globe, we are inundated with (photo-manipulated and literally unattainable) images of whatever the most conventional current representations of beauty happen to be, and almost no images of anyone outside the standard. Whether the marker is race, ethnicity, skin color, age, weight, class, ability, or anything else, those who do not come close to the conventional, unrealistic “norms” are, in our experience, hungry, often desperate, for attractive, respectful images of people they can imagine themselves being.

Each portrait suite includes a wide range of people in the group being photographed, including differences in age, race, ethnicity, class, size, etc. To accomplish this, we needed to show early photographs to the widest possible range of potential models, hear people’s suggestions and ask as many questions as we can think of: what do you want to see in these pictures? Who is missing? What kinds of images do you wish you had available? What do you have to say about the topic? What works? What doesn’t? What could we be doing better? We use the responses to these questions to continually refine and improve the work.

Over and over, during all three projects, when people saw photographs of people like themselves, or like people they cared about, they were deeply touched, which translated into a desire to work with us on the project. People became invested in seeing the work completed, and widely available.

People she knew introduced Laurie to models, from college professors to sewing-machine operators. Ideally, she and the prospective model would have tea, looking at some sample photographs and text and discussing the project. Very often the models had already been introduced to the work. She asked the models to decide where they wanted to be photographed. The places they chose reflected how they lived and perceived themselves. Laurie wants the portraits not only to convey a sense of the person being photographed, but also to provide a sense of their lives that went beyond a photograph taken in the moment.

This comment from one of the Women of Japan models is exactly what Laurie strives for:

I assumed that I would be asked to pose as a “model Ainu,” and so I prepared my traditional Ainu garment to be photographed in. And so when I was asked to pose as “My naked self” and as “a woman,” I felt suddenly quite nervous. To be honest, my real intention was to be photographed wearing the Ainu traditional dress. But, Laurie’s passion was communicated to me through the lens of the camera, your “naked self,” “pose as you like,” and yet I feel that my face was still quite nervous. Laurie said “relax” with a smiling face, and waited until I felt comfortable – I felt happiness from my heart. To sit or stand in front of a camera lens is no simple task, and this was definitely a good experience for me.

– Komatsuda Hatumi, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Both in the United States and in Japan, we most often speak and write about the fine art and social change aspects of our work, and in both places (including in this post) we have also been invited to speak specifically about our practices of community involvement and how they work.

Community outreach to groups you don’t personally identify with takes far more time, effort and creativity than outreach to “people like you.” Without thinking about it, you know where “people like you” gather, what general things they expect and want, what messages they will respond to. And they are inclined to trust you simply because they recognize you. “People not like you,” on the other hand, will by definition have different experiences, expectations and motives, and be slower to trust. And groups are always composed of individuals, and general assumptions about the group are dangerous. It’s all about taking time, building trust, watching and listening, being open to change how you do things because you value the input, and making the diverse involvement deep, long-term, and necessary to the project.

(A different version of this post is in our essay on “Body Image in Japan and the United States” for the journal Japan Focus.)