Back when pretty much the only men wearing makeup were either rock lords or Boy George, I privately came up with the guideline that if any particular piece of grooming was something women generally performed while men generally didn’t, I could safely consider it “beauty work.” Nail polish and leg-shaving? Beauty work. Nail-trimming and hair-combing? Grooming. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a useful guide in helping me determine what parts of my morning routine I might want to examine with a particularly feminist—and mascaraed—eye.

That rule has begun to crumble. Americans spent $4.8 billion on men’s grooming products in 2009, doubling the figure from 1997, according to market research firm Euromonitor. Skin care—not including shaving materials—is one of the faster-growing segments of the market, growing 500% over the same period. It’s unclear how much of the market is color products (you know, makeup), but the appearance of little-known but stable men’s cosmetics companies like 4V00, KenMen, The Men Pen, and Menaji suggests that the presence is niche but growing. Since examining the beauty myth and questioning beauty work has been such an essential part of feminism, these numbers raise the question: What is the increase in men’s grooming products saying about how our culture views men?

The flashier subset of these products—color cosmetics—has received some feminist attention. Both Naomi Wolf of The Beauty Myth fame and Feministe’s own Jill Filipovic were quoted in this Style List piece on the high-fashion trend of men exploring feminine appearance, complete with an arresting photo of a bewigged, stilettoed Marc Jacobs on the cover of Industrie. Both Wolf and Filipovic astutely indicate that the shift may signal a loosening of gender roles: “I love it, it is all good,” said Wolf. “It’s all about play…and play is almost always good for gender politics.” Filipovic adds, “I think gender-bending in fashion is great, and I hope it’s more than a flash-in-the-pan trend.”

Yet however much I’d like to sign on with these two writers and thinkers whose work I’ve admired for years, I’m resistant. I’m wary of men’s beauty products being heralded as a means of gender subversion for two major reasons: 1) I don’t think that men’s cosmetics use in the aggregate is actually any sort of statement on or attempt at gender play; rather, it’s a repackaging and reinforcement of conventional masculinity, and 2) warmly welcoming (well, re-welcoming, as we’ll see) men into the arena where they’ll be judged for their appearance efforts is a victory for nobody—except the companies doing the product shill.

Let’s look at the first concern: It’s not like the men mentioned in this article are your run-of-the-mill dudes; they’re specific people with a specific cultural capital. (Which is what I think Wolf and Filipovic were responding to, incidentally, not some larger movement.) Men might be buying more lotion than they did a decade ago, but outside of the occasional attempt at zit-covering through tinted Clearasil, I’ve seen very few men wearing color cosmetics who were not a part of a subculture with a history of gender play. Outside that realm, the men who are wearing bona fide makeup, for the most part, seem to be the type described in this New York Times article: the dude’s dude who just wants to do something about those undereye circles, not someone who’s eager to swipe a girlfriend’s lipstick case unless it’s haze week on fraternity row.

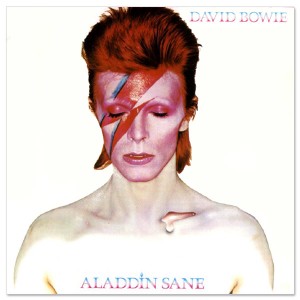

“Men use cosmetic products in order to cover up or correct imperfections, not to enhance beauty,” said Marek Hewryk, founder of men’s cosmetics line 4V00. Sound familiar, ladies? The idea of correcting yourself instead of enhancing? Male cosmetic behavior seems more like the pursuit of “relief from self-dissatisfaction” that drives makeup use among women rather than a space that encourages a gender-role shakeup. Outside of that handful of men who are publicly experimenting with gender play—which I do think is good for all of us—the uptick in men’s cosmetics doesn’t signify any more of a cultural shift than David Bowie’s lightning bolts did on the cover of Aladdin Sane.

Subcultures can worm their way into the mainstream, of course, but the direction I see men’s products taking is less along the lines of subversive gender play and more along the lines of products that promise a hypermasculinity (think Axe or the unfortunately named FaceLube), or a sort of updated version of the “metrosexual” epitomized by Hugh Laurie’s endorsement of L’Oréal.

The ads themselves have yet to be released, but the popular video showing the prep for the ad’s photo shoot reveals what L’Oréal is aiming for by choosing the rangy Englishman as its new spokesperson (joining Gerard Butler, who certainly falls under the hypermasculine category). He appears both stymied and lackadaisically controlling while he answers questions from an offscreen interviewer as a young woman gives him a manicure. “That’s an interesting question to pose—’because you’re worth it,’” he says about the company’s tagline. “We’re all of us struggling with the idea that we’re worth something. What are we worth?” he says. Which, I mean, yay! Talking about self-worth! Rock on, Dr. House! But in actuality, the message teeters on mockery: The quirky, chirpy background music lends the entire video a winking edge of self-ridicule. When he’s joking with the manicurist, it seems in sync; when he starts talking about self-worth one has to wonder if L’Oréal is cleverly mocking the ways we’ve come to associate cosmetics use with self-worth, even as it benefits from that association through its slogan. “Because you’re worth it” has a different meaning when directed to women—for whom the self-care of beauty work is frequently dwarfed by the insecurities it invites—than when directed to men, for whom the slogan may seem a reinforcement of identity, not a glib self-esteem boost. The entire campaign relies upon a jocular take on masculinity. Without the understanding that men don’t “really” need this stuff, the ad falls flat.

We often joke about how men showing their “feminine side” signals a security in their masculine role—which it does. But that masculinity is often also assured by class privilege. Hugh Laurie and Gerard Butler can use stuff originally developed for the ladies because they’ve transcended the working-class world where heteronormativity is, well, normative; they can still demand respect even with a manicure. Your average construction worker, or even IT guy, doesn’t have that luxury. It’s also not a coincidence that both are British while the campaigns are aimed at Americans. The “gay or British?” line shows that Americans tend to see British men as being able to occupy a slightly feminized space, even as we recognize their masculinity, making them perfect candidates for telling men to start exfoliating already. L’Oréal is selling a distinctive space to men who might be worried about their class status: They’re not “metrosexualized” (Hugh Laurie?), but neither are they working-class heroes. And if numbers are any indication, the company’s reliance upon masculine tropes is a thriving success: L’Oréal posted a 5% sales increase in the first half of 2011.

Still, I don’t want to discount the possibility that this shift might enable men to explore the joys of a full palette. L’Oréal’s vaguely cynical ads aside, if Joe Six-Pack can be induced to paint his fingernails and experience the pleasures of self-ornamentation, everyone wins, right?

Well—not exactly. In the past, men have experienced a degree of personal liberalization and freedom through the eradication of—not the promotion of—the peacocking self-display of the aristocracy. With what fashion historians call “the great masculine renunciation” of the 19th century, Western men’s self-presentation changed dramatically. In a relatively short period, men went from sporting lacy cuffs, rouged cheeks, and high-heeled shoes to the sober suits and hairstyles that weren’t seriously challenged until the 1960s (and that haven’t really changed much even today). The great masculine renunciation was an effort to display democratic ideals: By having men across classes adopt simpler, humbler clothes that could be mimicked more easily than lace collars by poor men, populist leaders could physically demonstrate their brotherhood-of-man ideals.

Whether or not the great masculine renunciation achieved its goal is questionable (witness the 20th-century development of terms like white-collar and blue-collar, which indicate that we’d merely learned different ways to judge men’s class via appearance). But what it did do was take a giant step toward eradicating the 19th-century equivalent of the beauty myth for men. At its best, the movement liberated men from the shackles of aristocratic peacocking so that their energies could be better spent in the rapidly developing business world, where their efforts, not their lineage, were rewarded. Today we’re quick to see a plethora of appearance choices as a sign of individual freedom—and, to be sure, it can be. But it’s also far from a neutral freedom, and it’s a freedom that comes with a cost. By reducing the amount of appearance options available to men, the great masculine renunciation also reduced both the burden of choice and the judgments one faces when one’s efforts fall short of the ideal.

Regardless of the success of the renunciation, it’s not hard to see how men flashing their cash on their bodies serves as a handy class marker; indeed, it’s the very backbone of conspicuous consumption. And it’s happening already in the playground of men’s cosmetics: The men publicly modeling the “individual freedom” of makeup—while supposedly subverting beauty and gender ideals—already enjoy a certain class privilege. While James Franco has an easygoing rebellion that wouldn’t get him kicked out of the he-man bars on my block in Queens, his conceptual-artist persona grants him access to a cultural cachet that’s barred to the median man. (Certainly not all makeup-wearing men enjoy such privilege, as many a tale from a transgender person will reveal, but the kind of man who is posited as a potential challenge to gender ideals by being both the typical “man’s man” and a makeup wearer does have a relative amount of privilege.)

Of course, it wasn’t just men who were affected by the great masculine renunciation. When men stripped down from lace cuffs to business suits, the household responsibility for conspicuous consumption fell to women. The showiness of the original “trophy wives” inflated in direct proportion to the newly conservative dress style of their husbands, whose somber clothes let the world know they were serious men of import, not one of those dandy fops who trounced about in fashionable wares—leave that to the ladies, thanks. It’s easy, then, to view the return of men’s bodily conspicuous consumption as the end of an era in which women were consigned to this particular consumerist ghetto—welcome to the dollhouse, boys. But much as we’d like to think that re-opening the doors of playful, showy fashions to men could serve as a liberation for them—and, eventually, for women—we may wish to be hesitant to rush into it with open arms. The benefits of relaxed gender roles indicated by men’s cosmetics could easily be trumped by the expansion of beauty work’s traditional role of signaling one’s social status. The more we expand the beauty toolkit of men, the more they too will be judged on their compliance to both class markers and the beauty standard. We’re all working to see how women can be relieved of the added burden of beauty labor—the “third shift,” if you will—but getting men to play along isn’t the answer.

The Beauty Myth gave voice to the unease so many women feel about that situation—but at its heart it wasn’t about women at all. It was about power. And this is why I’m hesitant to herald men spending more time, effort, and energy on their appearance as any sort of victory for women or men, even as I think that rigid gender roles—boys wear blue, girls wear makeup—isn’t a comfortable place for anyone. For the very idea of the beauty myth was that restrictions placed upon women’s appearance became only more stringent (while, at the same time, appealing to the newly liberated woman’s idea of “choice”) in reaction to women’s growing power. I can’t help but wonder what this means for men in a time when we’re still recoiling from a recession in which men disproportionately suffered job losses, and in which the changes prompted in large part by feminism are allowing men a different public and private role. It’s a positive change, just as feminism itself was clearly positive for women—yet the backlash of the beauty myth solidified to counter women’s gains.

As a group, men’s power is hardly shrinking, but it is shifting—and if entertainment like Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and the Apatow canon are any indication, that dynamic is being examined in ways it hasn’t been before. As our mothers may know even better than us, one way our culture harnesses anxiety-inducing questions of gender identity is to offer us easy, packaged solutions that simultaneously affirm and undermine the questions we’re asking ourselves. If “hope in a jar” doesn’t cut it for women, we can’t repackage it to men and just claim that hope is for the best.