After the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville — ostensibly a protest of plans to remove the statue of Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park, because we all totally believe that that was their motivation — many cities have started removing their own statues glorifying Confederate figures. Baltimore removed statues honoring Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Confederate women, and Roger B. Taney (author of the Dred Scott decision) all in one night. Birmingham encased the Confederate memorial in Linn Park in plywood — as Alabama state law prohibits removing it outright without, essentially, written permission from God himself — until the city can decide on a longer-term solution. (The state has sued anyway, with a potential penalty for Birmingham of $25,000.)

Confederate statue enthusiasts have argued that removal of such statues amounts to an erasure of history. We can’t erase history! they insist. These statues have to remain so we can remember how bad slavery was. (They never explain how an obelisk for the “heroes” who died “fighting for white supremacy” reminds us that slavery is bad, but I’m sure someone will get around to it.) But believe it or not, there are ways to memorialize difficult, painful, and contentious parts of history without glorifying, for instance, generals who led the wrong side of a war to perpetuate slavery. Birmingham’s Kelly Ingram Park (itself named for a fallen war hero, the first Navy sailor killed in World War I) provides several examples of different ways to do this with statues and sculptures memorializing the Civil Rights movement. Individually and collectively, they send the message that bigotry is bad, and equality is good, and fighting for freedom is noble, all without putting a single mass-produced Confederate general on a literal pedestal.

Police Dog Attack (1993) (Photo credit American Studies Journal)

Police Dog Attack (1993) (Photo credit American Studies Journal)

This sculpture represents the snarling police dogs set upon nonviolent protesters during the Civil Rights movement. When you’re making a “never again” memorial, the trick is to not make the bad guys look majestic. (Similarly, this one does not declare the man or the dog depicted to be a hero in the fight for segregation.)

Four Spirits (2013) (Photo credit Kill the Jellyfish)

Four Spirits (2013) (Photo credit Kill the Jellyfish)

The Four Spirits sculpture is a memorial to Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Denise McNair — the four girls killed in the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963. It reminds us of the bombing, and it makes it clear that it was bad by showing us the lives that it took. (And I don’t think anyone could disagree that it’s a truly beautiful monument.)

Martin Luther King, Jr. (2010) (Photo credit Library of Congress)

Martin Luther King, Jr. (2010) (Photo credit Library of Congress)

This statue of Martin Luther King, Jr., is an example of the common practice of building respectful, dignified statues of people who are admirable and can be taken as a positive example. (There’s also this one memorializing student protesters for their courage and fortitude.)

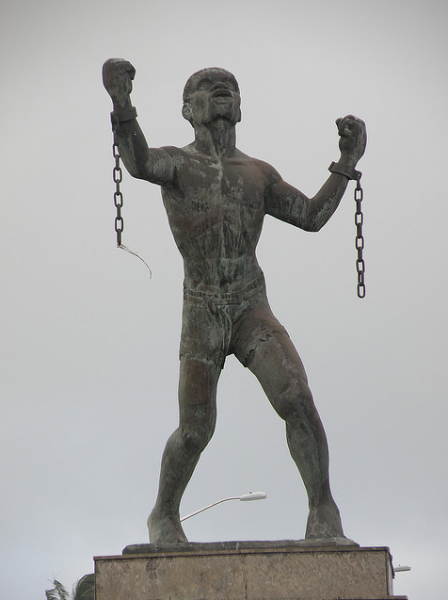

Emancipation Statue (1985) Photo credit Dogfacebob)

Emancipation Statue (1985) Photo credit Dogfacebob)

This statue isn’t in Birmingham — it’s in Barbados — but it’s another good example of a statue that commemorates history without any equestrian generals. The Emancipation Statue depicts a slave (the locals call him Bussa, for a slave who inspired a slave revolt in 1816) breaking his chains to start a rebellion. It commemorates the abolition of slavery in Barbados in 1834. Because it’s honoring a good thing, it’s depicting the people benefiting from that thing, and it’s showing them in a posture of power. If the statue was of a slave owner looking contemplatively out toward the horizon, it would miss the point that enslaving people is bad and freedom is good, so it avoids that trap by not doing that.

Confederate statue fans can rest easy in the knowledge that moving those 20-foot-tall equestrian statues of Confederate generals to museums or private land will not erase, deny, or whitewash history. There are other ways of preserving it. (We haven’t even talked about books here.) The past will not be forgotten, leaving us in danger of oopsidently starting slavery again because the statue of a man who fought to preserve it was the only thing reminding us that it’s bad.